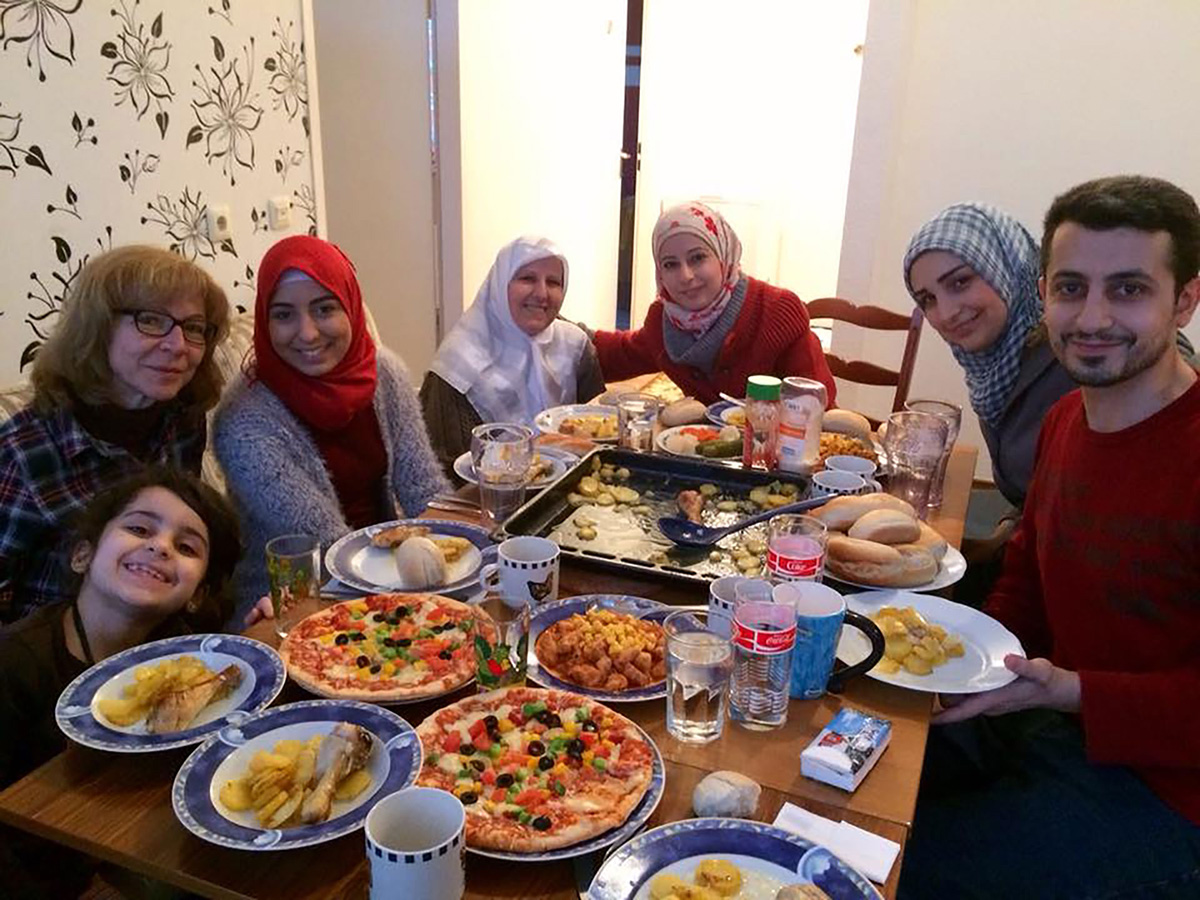

Noura was rescued by MOAS in January 2016. Now, she is building a life in Germany with her family.

Noura was rescued by MOAS in January 2016. Now, she is building a life in Germany with her family.

Welcome back to MOAS…The last time you joined us we were hearing the stories of people we’ve rescued.

Now, let’s take you from the Mediterranean and deep into the heart of Europe, to the Gothic city of Erfurt, Germany. Over one million asylum seekers have sought refuge in Germany in the last two years, with Erfurt welcoming its share. In this episode we’re going to talk to some of those refugees currently living in the city and the organisations helping them to integrate.

Eman is a thirty-year-old Syrian from Damascus. She came to Erfurt with her family back in 2014. This was her first time in Europe. She didn’t want to be her, but she had no choice. The locals welcomed them in; “they liked to help us”, she says.

Before the revolution I could never say it was perfect because we didn’t have freedom there. We had what we needed but it’s very hard to live when you need to speak out, to speak loud, to say what your opinion is, to do what you like to do. It’s a little bit hard but of course it was a good living, we had food, we had hospitals, we had everyday needs.

We left in 2013 two years after the revolution. It was very hard to find a doctor. In our city we had just one hospital and at that time there were maybe three or four doctors. My father had an accident and it was very hard to find him a doctor to treat him and to find him medicine.

One of the reasons that made us leave at that time was because we expected the military to come at any time to our home because they have no time, they have no rules. They could come at any time, they could just break the doors and just go in. So it was like you were always expecting something at night or during the day. That was in 2013 when we left.

How did you find coming to Germany?

When we were in Istanbul that for us was a little bit like our home, because although we don’t have the same language, we do have the same religion, the same history so it wasn’t far away from us. It wasn’t a bad feeling living in Istanbul. But coming to Europe was like the end of the journey for us, we left everything behind, we left our history, our home, everything that mattered we left behind and we came to Europe. I was never in Europe before, this is my first time.

When we came to Germany I wasn’t so happy because that was for me like the end: I will never go back. But I believe and I still believe that if we have to find a new home, we have to find a new place to fight for our country a little bit. We can’t just lose our country without fighting that’s what I believe. When we could hear a new life starting then we could fight again for what we believe, for our country, for us.

What were the biggest challenges you faced when you first arrived?

First of all it was the language, of course. It’s a new language for us. We are in West Germany in Erfurt, the people here don’t speak English, they don’t like to speak in another language. Wearing hijab and covering our heads was our second challenge here in Erfurt. We didn’t feel welcome. We feel different, we wear different, we speak different. We try to not be different but we couldn’t help it, but we are different. We come from another country, we come from another culture, we come from another community, so we are different we can’t help it. Actually we spent the first year in depression, we couldn’t do anything in the first year here because it was very hard feeling not welcome in some places and we know we have no any other chance, we can’t go back, we are here in Europe but its hard for us to stay in Europe.

But when we started to learn the language and make friends here and getting to know the difference between the people who welcome us and those who don’t like us and everything start to be different, we start to understand the community. At least at the beginning we felt it was hard because we knew that this would be our new home for the next 20 years or so. It’s just maybe our problem in the beginning and I believe now everything is better actually. We’re still facing the same situation, we’re still facing the same people who don’t like us, everyday we still face the people who don’t accept us being in their country but we learn how to deal with it.

Almost 3 percent of all refugees in Germany are transferred to Thuringia, the region Erfurt sits in. Once asylum seekers make an application they have to stay in their allocated region for three years. Dr Duncan Cooper is a consultant working for the Thuringia Commissioner for Integration and Migration.

Can you give me an idea of the demographic of the refugees coming to Erfurt?

In 2015 there were almost 30,000 refugees who came to Thuringia the region, which is the highest number who have ever come to the region since German reunification. That rose from about 4,800 in 2014 and it fell last year to about 6,600 because of the changing situation and political situation, I guess, which is still considerably higher than the long term average. As regards the demographic situation, we see that large numbers of these migrants and refugees are actually quite young. I think it’s a large proportion are under 25. As far as the main countries of origin, we see Syria 42%, Afghanistan 25% Iraq 17%, the three main countries. The fourth country is Eritrea with 4%.

How do civil society organisations fit into the wider government policy on refugee and migrant integration?

They supplement and complement the integration measures which are supported and coordinated at state and regional level by state authorities, and I say they play a crucial role. Large numbers of volunteer groups were spontaneously founded in 2015 and 2016 off the bat and as a result of this large increase in the number of refugees coming to this country and the images that people were seeing on the television.

They play a crucial role. It’s important to state here that these initiatives came really from the grassroots level they were spontaneously organised. What we do is interesting, actually in Thuringia, the Commission for integration and migration of refugees we actually employ three people who actively support the voluntary refugee helpers and provide them with help and information, and we actually published in February a handbook for volunteers which contains useful information regarding contact persons, access to state assistance and other useful information.

What integration programmes do you operate or cooperate with?

Well you have to distinguish here between the federally funded integration programmes and those which are funded and coordinated at a regional level. The main integration measure carried out or coordinated at a federal basis are the integration courses. It’s 600 hours of German language instruction and 100 hours of social societal orientation and these courses are run by local institutions but actually coordinated and funded by the Central state. All asylum seekers there who have been granted asylum and those whose claims are being processed and have good prospects of remaining in Germany are allowed to participate in these integration courses. What is interesting is that those asylum seekers who have medium and poor prospects of remaining in the country, and those whose claims have been rejected, aren’t allowed to take part in these courses, which is why then the department of the migration ministry here in Thuringia has decided to put a course into place called ‘StartDeutsch’ – ‘Start German’ which allows people who their claims have been rejected or have medium or poor prospects of remaining in the country to learn German while their application is being processed.

As well as the language we also have different other integration measures. The state government funds first counselling for adult migrants and also youth migrants. Those are things which are coordinated and carried out by other non-governmental health organisations but are actually sponsored by the central state. Then we have integration through qualification, and again that’s funded by the state and the European social fund aimed at integrating migrants at a local and regional level. Also at a regional level we also have other different measures aimed at integrating migrants such as projects which we fund projects aimed at the integration process. We also have something called labour market preparation year with language assistance which is aimed at helping refugees to obtain or get into the apprenticeship market, to try and get an apprenticeship by preparing them on apprenticeship in Germany whilst giving at the same time language assistance. So there’s a range of measures.

So, there’s no limit to the efforts to welcome refugees into Thuringia. Let’s talk to one programme in Erfurt, the Spirit of Football. The programme employs refugees and volunteers from the local university and runs projects across Germany. They use football to bring refugee and local communities together. Andrew Aris is its founder.

We set up the Spirit of Football 10 years ago, we’re a non-profit organization in Erfurt here in Germany. I set up the Spirit of Football, I had the idea during my Masters studies here, Masters in Public Policy to found a non-profit organization that was to try and use the Football World Cup that was coming to Germany in 2006. In 2005 I set up Spirit of Football with six other people to use the World Cup to try and promote the city of Erfurt, to bring people together to help to promote Erfurt as a city that embraces multiculturalism by using the sport of football which is my passion, my life. Up until that point I’d always played football and met lots of people. Growing up in New Zealand you see that the world plays this sport and being quite isolated from the rest of the world football was a chance that allowed me on my travels to connect with people it didn’t matter which country I was visiting, you could kick a ball with people, meet people and make new friends. With that in mind I wanted to set up an organization that used the positive power of football to bring people together and connect people in this city of Erfurt where I was living at the time.

Tell me about some of the projects you run…

So on Tuesdays we have sports training in the afternoon and evening, Wednesday evening is a culture evening where we have 90 to 100 people come together, we cook together, we eat together, we play games together, we have presentations, we watch football from time to time. Thursdays we have training for under 18 year old refugees. We have Friday futsalz sessions as well as lots of other events. From the few thousand refugees that are in Erfurt we would’ve worked together with about 30% of them at least. Most of the refugees that have come to us are from Syria, others from Afghanistan, Somalia also from other African countries and mostly young males, but we also have a really fantastic project that we’ve recently set up which is a women’s bike project where we get bikes donated and we fix them up and we teach these actually young female students teach women and girls how to ride bikes and this is a great inspirational project because it allows them to learn a very important thing in Germany that is bike riding, it’s a very strong cultural asset I would say and they get on their bikes. At first thing, ‘I can’t do this’ then the empowerment of learning how to ride a bike then the access that you get to the city and the connections that you make has really been fantastic.

How do you think the Spirit of Football has helped refugees integrate?

I would say it’s helped enormously and that people are very grateful for what we’ve done. One has to think that on Wednesday evening there was a time, they’re not doing it these days thankfully but the AFD (Alternativ Für Deutschland) is this right wing political party with a leader in Thuringen called Björn Hück e who is quite a dangerous character and they were having their rallies on a Wednesday night and gathering a few thousand people which was very very scary and was at the same time as our cultural evenings were taking place on a Wednesday evenings, and they still are. It was like offering this safe family friendly environment where people could come together and just feel at home and the feedback we were getting, the Spirit of Football is a home away from home, the so-called Veschdahaus where our association is based, our cultural house was just this point where people could come together and really feel like they are at home and with friends.

The point was also that with everything that we were doing if it was football, if it was whatever courses that we were offering we were trying to speak in German to enable an opportunity to have an exchange in the German language so that the refugees could improve their German and just through this whole network that we offered them they were connecting to football clubs, to other sports clubs, to freetime activities, to events where they knew they could come and feel at home and connect with other local people and the network that’s been created is significant I think. I’m sure there are similar things going on, I know there are similar things going on in other towns and cities but I think what we’ve got is quite unique. So it’s been significant for us to see this develop from arrival, uncertainty, finding a home, feeling welcome and learning the language and connecting to our network and helping to grow our network now and also being really part of everything we do and really feeling part of it.

Two of Andrew’s friends are Tarek and Siddiq. Both are refugees in Germany.

My name is Tarek Esmail (Esmaiell) I’m 29 years old and I’m from Syria, from Aleppo City.

My name is Mohamed Siddiq I am from Afghanistan in Herat Province and I’m 33 years old.

Tarek is an English teacher and translator from Aleppo while Siddiq is a father of 7 and a former translator for American forces in Afghanistan. Their journeys to Germany are similar… fast paced and dangerous.

Tarek: My journey to Germany was kind of interesting, fast and very very dangerous in the sea. Let me say, the most dangerous three hours in the sea I have spent. It’s not because I’m afraid for my life it was just there was a two-month year old girl in the boat I was in and I was, in the three hours just concentrating on this girl. I don’t know, let me say, I’m a young man, I’m alone, I can manage it but how can this young girl and her family manage it. I have seen so many pictures, so many videos before I go to Germany of the people who die on the shore. So, these pictures start to come to my mind. Thank god after three hours we could do it and we just arrived to Greece and it was like coming to Paradise. It was like the hardest part of the journey is finished, safe without any problem.

After arriving in Greece I spent five days and when you compare these five days with others, this is very short journey. Some people spend one month, others spent two months. The most horrible moments were when we wanted to cross the Hungarian border because all the people told us how dangerous it is to be in Hungary as a refugee, as an illegal person crossing their border. I spent in Hungary just 6 hours, I crossed the border, there were no police or let me say, they did not even see us. I went directly to the main train station, then we got a ticket directly to Austria. Then we just crossed it very very safe. From Austria we found some buses waiting for us and there were so many people also waiting with us, 1,000s of people. We had to wait hours to get a bus for us. The bus took us directly to Germany it was like ‘thanks god, it’ s finished, I’m in Germany now’.

Can you tell me a little about your asylum experience and what you’re doing now?

Siddiq … eventually we had a bus and the bus took us from München to Messehalle, Congress Centre. So I was there for almost 26 days then when I see some of the German guys working as volunteers, so everyone was coming to help the refugees. They would finish work and come to help the refugees for one or two hours as a volunteer. This was a great experience and I got skills from them. Then I think to myself, ‘oh Siddiq, you know so many languages, these guys are very tired, they come from their jobs and help us. I should help, I’m here, I should help others’. Then I start working as an interpreter/translator. I was translating for the different people like from Syria, I can speak Arabic, I can speak my native is Pashtun, Dari, Farsi.

So I can speak these languages so then I start to work as a translator, then I was in Messehalle for 26 days then I worked voluntarily as an interpreter. Then they transferred me to ‘Bonn Zentrum Assenheim’ in the same city of Erfurt, it’s not far from Messehalle. I have been here almost 17 or 18 months and still I live in a refugee town. I am now starting to look for a house and I’m searching for a job as well. I’ve already applied for Zalando because I don’t want to get money from the job centre. That’s shameful for me that I would take money from the government. I have to work by myself and the government almost paid for two years so I have start earning money by myself. I have to pay for my house, I have to pay for everything, my insurance, health insurance, my food and everything. If I stay at home and I start my German integration course. I just finished ‘Eins’ (One) Buch. I had a plan to learn more but still I can solve my problems in the German language as well. I mean not all the problems but I mean I can run my life and how to deal with the people and how to communicate with the people.

What does it feel like being away from home?

Tarek: I did not see my mum in 5 years and you know that moment when you leave a place and start looking behind while you’re leaving. I was just watching my mum she was just looking at me. I was a heartbreaking moment. I never expected that I would not see my family for 5 years, I’ts maybe more even. I thought I could go at least to visit, once a month or once a while. Now I can’t even visit them, or see them just through Whatsapp call. I can hear their voices through the internet. It’s a kind of harsh feeling. For the hard thing we are facing here in general in Germany; racism, the first, bureaucracy, also here, I had to wait 6 months until I could get a language course. So I was just for 6 months trying to do something to find some activity. That was the hardest thing. My feelings? For my family and how the situation here in Germany. But it’s also OK, it’s nice.. there are so many nice people, so many people are helping. After one and a half years we’d got so many friends here in the city we’re trying to do a lot to help or do activities or job, or learning languages.

What are your hopes for the future?

Siddiq: My hopes are that I can get together with my family, with my kids and they get an education. One of the most important hopes is that they get to go to school, they get an education and they can be a service to society. If they grow up without an education, if someone is not educated he doesn’t know himself, if he doesn’t know himself or herself it means he doesn’t know other people’s values. So education is the most important part of life so this is my hope that my kids have to go to school and they have to make a service for society. But now they are growing up without an education so that’s the big issue that makes me worried. I worry about my kids. I hope that I will bring my kids and they will get an education and they will be together with me. I’m not an old man, I’m 33 years old so it’s very difficult to be away from the wife for 2 or 3 years so everyone has so many desires. So if work for the whole day and I come back and I see my kids and my wife it means all the tiredness will be finished. If I go to work and I come to my house and I see just only my bed and my pillow without wife, without kids, its just not big enough for my mind, so I have to get together with my wife and my kids and get education, this will be a great day in my life.

For many refugees Germany is their new home, they can’t go back. Some are dealing with this future while others are not. Germany is Eman’s new home… it’s a place to fight for Syria and one day she hopes to go back… to her room

For me, and the people who are similar ages with me it’s not very hard for us to deal with it because we know that we may never have another chance to change our lives or to do something in our lives. It’s not a good feeling know you’ve lost your home, you’ve lost the place you belong. We will never move on we will just deal with it, we will just understand that we are living here now, we are acting like this is our home but it will never be because we still believe that we have a home, I still believe I have a home and I still believe one day I will go back to my room. I still believe that what we are doing here will help Syria in one way or another. That’s what makes us stronger actually, to feel that we are not just fighting for us we are fighting for something bigger we are fighting for our country and we are fighting for our people. To be here in Europe and to be successful here in Europe means you are Syrian and you are successful and you’ll be someone helpful one day.

Next week on the podcast… We’re heading to the Valletta Film Festival for the screening of the MOAS documentary, Fishers of Men… We’ll be chatting with the creators and getting reactions from the audience.

Until then you can follow us on our social media. Check out our latest updates on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Youtube and AudioBoom… or you can support our rescue missions by giving whatever you can to help us save lives at sea. From all of us here at MOAS: goodbye.

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained.