Hello and welcome to MOAS…

What is humanitarianism? It’s about providing an immediate short-term response to the needs of vulnerable people, easing their suffering during a crisis, natural or man-made.

It takes the form of delivering food aid, water, shelter and life-saving medical care to tens and hundreds of thousands of people, and more. The organisations doing it vary in size, and are founded on the principles of Humanity, Neutrality, Impartiality and Independence.

That’s just one interpretation, but Humanitarianism is changing. In this podcast we’re exploring these changes, responding to modern challenges, possible blurring with its longer-term cousin, development and the concerns of innovation and technology.

The first humanitarians as we know them, appeared on the battlefields of the mid-19th Century. Witnessing the carnage of the Battle of Solferino in 1859, Swiss businessman Henri Dunant organised efforts to care for the injured on both sides, a battle affecting 23,000 men.

The International Committee for the Red Cross was born and it would go on to provide medical support to both soldiers and civilians in conflict zones across the world. Fast forward 150 years and conflict has changed dramatically, forcing humanitarianism to adapt to new contexts. Claudia McGoldrick is Special Adviser to the President and Director General of the International Committee of the Red Cross…

‘There are about an estimated 50 million people living in situations of drawn out urban violence and also urban violence in situations outside of situation of warfare. For example, in parts of Latin America, the levels of organised crime and organised violence in many cases is more deadly than classic armed conflicts. So when you have this type of violence and conflict and combined with other crises such as natural disasters, increasing environmental pressures, climate change, social and economic problems.

If we think back to the Arab Spring which it’s fundamental reason or cause for that was rising food prices in various affected countries, then we have a situation of chronic hardship, weakened resilience if you like were people are less to resist to sudden shocks and in some cases whole regions affected with vast numbers of people. If we think of the Sahel region, Mali, parts of Niger, Burkina Faso and also parts of the Horn of Africa. We’re talking about vast areas and vast numbers of people affected and we’ve seen that very clearly with the current migration crisis if you can call it that. But, that’s just one symptom that we’ve been seeing in Europe and elsewhere, of these conflicts that have been going on in many cases, for a long time.

Another challenge is that parties to the conflict have themselves changed. We now have very complex webs of non-state armed groups in some contexts as dozens of armed groups, its sometimes very difficult to know who is fighting who, what their motives are and then certainly for ICRC as a humanitarian organisation to engage in dialogue with them is very challenging. States too, state parties to conflict, they’re becoming more and more assertive with their sovereignty, in many cases trying very hard to control humanitarian aid, direct it, ultimately politicise it.

Another factor too, the method and means of warfare have drastically changed. I mean, obviously there’s been massive advances in recent years and we’re seeing more and more autonomous weapons, for example, drones, increased risks from cyber war, these things have very important implications for International Humanitarian Law and how parties are held to account and how war is waged. All of this I would say has massive implications for humanitarian response. These long-term humanitarian consequences have major practical implications for humanitarian organisations, and is changing in many ways the way they respond.

Lastly, I think what is an important thing to mention here is the perception of victims or beneficiaries of humanitarian aid is also an important factor that is forcing humanitarian response to change, we no longer talk about victims or beneficiaries and in fact people affected by crisis, by conflict. As technology and communication technology has improved, they are demanding a much more central role in deciding how humanitarian aid is given to whom and in what form, so their role is forcing a very fundamental re-think particularly for international humanitarian organisations like the ICRC.’

How distinct are the actions of humanitarian organisations from development ones these days or are they too blurred?

‘ICRC’s 15 biggest operations have lasted on average 30 years which is obviously not short-term conflicts so the needs that emerge clearly go beyond immediate classic life-saving needs, so there’s humanitarian needs which extend to maintaining services, maintaining healthcare services, helping to ensure access to education, other aspects of community development.

So obviously with these kinds of long-term needs, yes, in some respects the humanitarian-development divide can seem quite artificial or blurred, yet, there are still very distinct funding mechanisms for humanitarian aid and development assistance and also fundamentally different aims. Development is inherently political. It aims to change society structures and governance, whereas humanitarian action is focused more on alleviating suffering of people and communities and by upholding and supporting services and infrastructure where that’s necessary.

So clearly there is a need for a re-think or reform of some of the strictly separate funding mechanisms and there are efforts underway. The UN’s so-called ‘Grand Bargain’ for example is one initiative that is attempting to have a more holistic approach to people’s needs and make funding mechanisms more adapted. There is also a need for closer cooperation between development and and humanitarian actors in some cases, that much is clear. But, it’s also important to stress that there is still a need for principled humanitarian action for neutral independent, impartial humanitarian action.

This can’t just be just subsumed if you like, into a larger model of aid, and it remains particularly important in some of the most difficult and challenging contexts of armed conflict and situations of armed conflict where in many cases, development actors can’t or won’t go. So, in these kinds of environments there is still a very important need for principled humanitarian action and that will never be blurred or mixed with development approach.

So, we see that humanitarian action is more long term in its approach, affected by political and technological changes along with the needs and views of those receiving it. But, what about the process of finding new ways of doing humanitarian work?

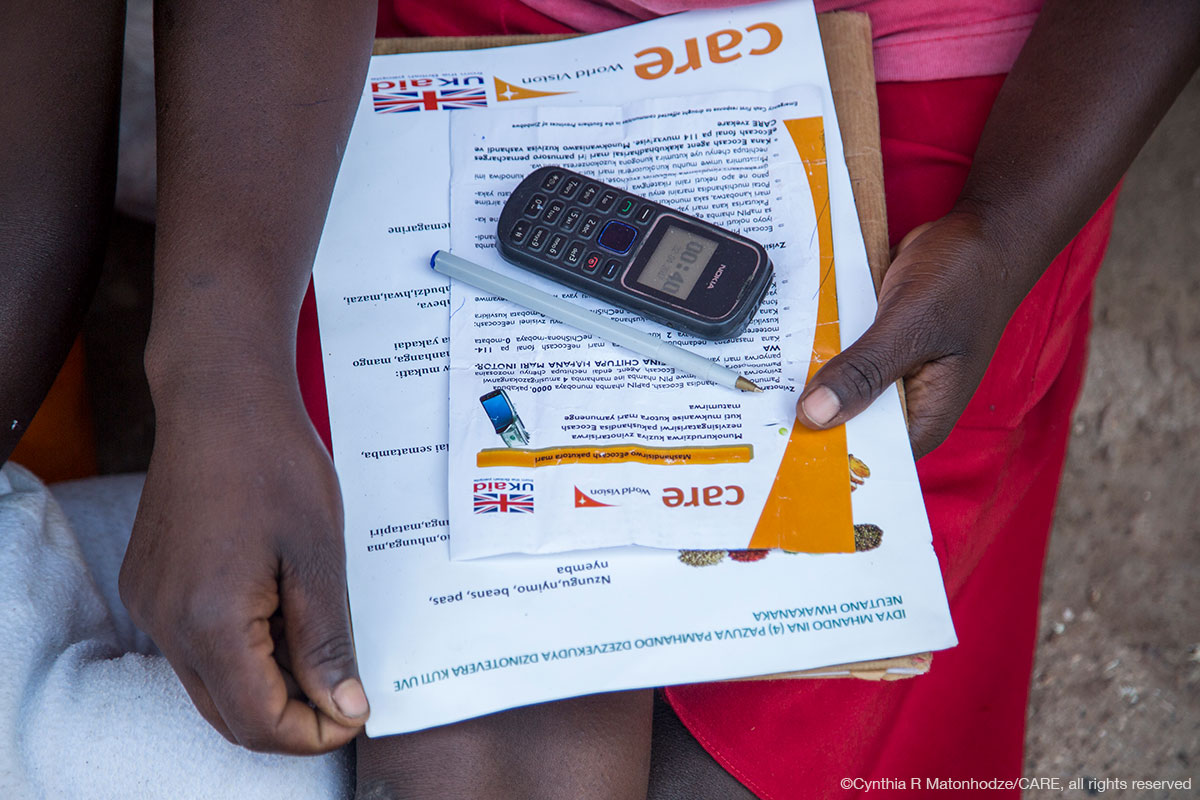

Innovation in humanitarianism is a subject Tom Newby, Head of Humanitarian for CARE International UK, has been trying to explore. In his view, innovation is this field needs to be viewed critically.

‘So what innovation means is very difficult and actually the blog I recently published on this, one of the comments that somebody had posted on it was that I hadn’t actually defined innovation so it wasn’t clear what I was talking about. That’s possibly part of its problem but also part of the opportunity with is it can be almost anything in a humanitarian context so I can be different approaches to do things and all about changing processes, it can be new technologies, new software, it can be all sorts of things.

Most of the organisations that talk about innovation have a pretty broad definition of what they mean by innovation. For me, the biggest area where we probably need innovation is in the processes and the ways we do things rather than the technological innovation, which is the area where people focus on because you can do technological innovation in a small project and you can get to a result relatively quickly. Whether it works or not is a different question. But, actually the most game changing innovation is potentially around big changes to how we do things and what we do and a lot of that might mean organisational change as well.

So, it can be all sorts of different things and its actually very difficult to define and I’m not sure where you would put the red line around what’s innovative and what isn’t. Of course the price we pay is that almost everything these days gets described as innovative because that’s what that’s people want to hear and there’s a perennial trap that we keep reinventing the wheel and actually if you go back to projects that were done 20 or 30 years ago, you’ll see that things we were talking about as new were tried then and probably with a different name but there’s very little that is genuinely new.

The most successful innovation I’ve ever seen is where the starting point actually comes from necessity and we have a problem and we have to overcome it otherwise people will suffer and things won’t get done and people come up with new and different ways of approaching those problems. That’s somewhere you see it happen again and again and again.’

Taking this further, can new technology help humanitarians work better with refugees? Dr Jeff Crisp says bring on the new ideas and the data collection but let’s not forget the people we’re helping.

‘I wouldn’t want to come across as too much of a Luddite on this issue. I fully agree that data collection and analysis as well as the introduction of new technology, has a very important role to play in addressing refugee issues, migration issues and humanitarian issues more generally, and in that sense I think it’s very positive that a number of organisations, particularly UNHCR, IOM and the World Bank are investing quite heavily in this area. So, I have no quarrel with the idea of using data and data analysis as a basis for effective refugee protection and humanitarian action but I do think we need to see the data issue in a broader perspective and in that context, I would make three particular points.

Firstly, there are some very important confidentiality and security issues related to data collection especially when it involves a collection of bio-metric data. We’ve seen situations for example where Syrian refugees are very worried that data collected on them might be sent back to the regime in Damascus and this will have very negative consequences on their return. I think we need to be very sensitive to these confidentiality and security issues especially as they relate to refugees.

Secondly, to come back to the very purpose of humanitarian action that we discussed earlier, let’s go back to the question of dignity. I think that there is a danger that the way in which data is collected does not do anything to support the dignity of refugees. I think refugees are told why data on them is being collected, they need to know what that data is going to be used for and most importantly of all, they need to be told who that data will actually be shared with.

My third point would be simply to suggest that it’s a fallacy to believe that data alone leads to effective and equitable policies. In fact, if you look at refugee and migration policies around the world, you will often find that those policies whether adopted by governments or international organisations are based on a wide range of variables, data is only one of the variables that are taken into account when policies are being established, we shouldn’t lead to the conclusion that if you have good data, you’ll automatically get good policies.

Finally, rather than talk about data I would rather talk about evidence and evidence can be collected in many different ways collecting statistical data and analyzing it is of course one way in which you can collect and make use of evidence, but there are many other ways. At the other end of the extreme for example, somebody called Graeme Rodgers, an anthropologist, has written a very interesting article which he talks about ‘hanging out with refugees’, and he simply means sitting down, talking to people, having a coffee with a refugee, getting to know them, getting to understand their hopes, their concerns, their aspirations, their intentions for the future. He would argue that this is just as valid a way of collecting useful evidence on which humanitarian action can be based, than the analysis of statistical data.

So yes, let’s go ahead with the introduction of new technology, let’s go ahead with the improved collection of analysis and data, but let’s see it in the broader context in the way in which we can understand the people we’re trying to help in terms of humanitarian action.

Humanitarianism is changing. If conflicts continue to displace people, there will always be a need for humanitarian action. But, how these organisations mold themselves to cope with increasingly protracted crises is another question. Equally, changes in the way they do things shouldn’t forget the people they’re helping.

If you liked this Podcast don’t forget to hit like, comment and subscribe for more Podcasts from us.

You can also follow us on our social media. Check out our latest updates on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Youtube and AudioBoom… or you can donate to help us help Rohingya refugees .

From all of us here at MOAS: goodbye.